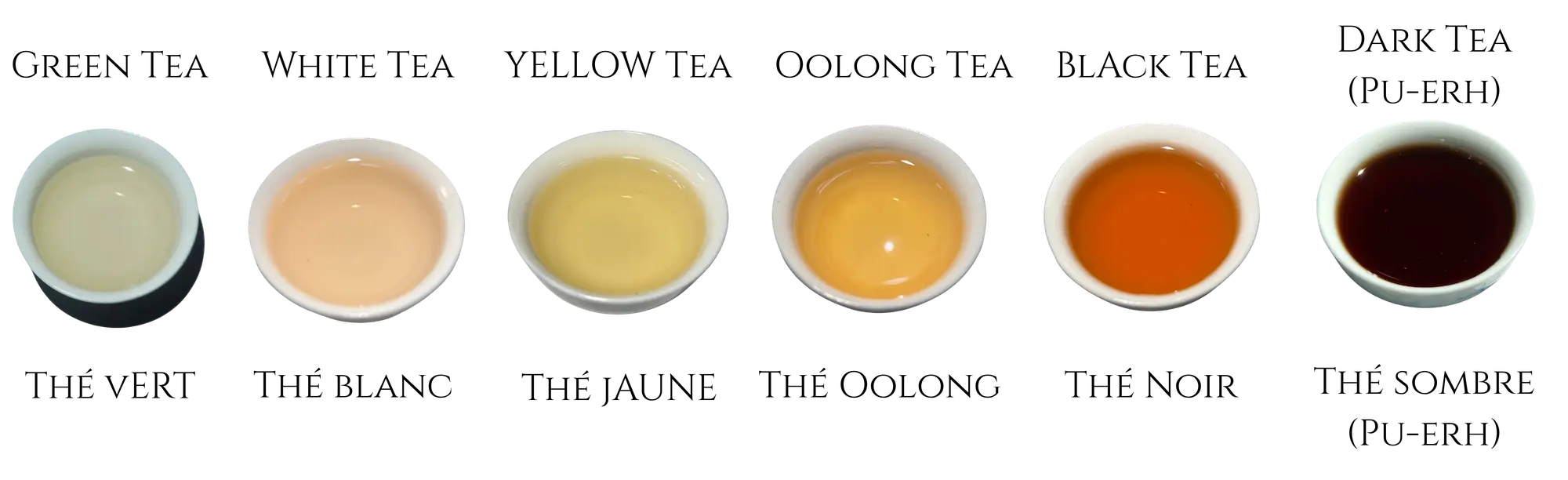

When most people think of tea, they usually picture black tea (as in an English Breakfast or Earl Grey), green tea, and sometimes oolong or white tea.

But in China, the birthplace of tea, experts classify teas into six major categories, based on how the leaves are processed and how much they undergo oxidation (sometimes called “fermentation”).

That’s right! One humble tea leaf can transform into six kinds of tea. What’s in your cup—green, black, white, or yellow—might simply be different destinies of the same leaf.

Of course, in practice, different varieties of tea leaves are often chosen for different teas.

(Think about wine, it won’t be difficult to understand).

Understanding this system not only helps you appreciate the diversity of Chinese teas, but also explains why teas can taste so different — from light and grassy to rich and earthy.

Green Tea

Oxidation: 0% (enzymes are deactivated right away).

Processing: Fresh leaves are heated quickly (pan-firing or steaming) to stop enzymatic activity, then rolled and dried.

Flavor: Fresh, grassy, vegetal, sometimes slightly astringent.

Examples: Dragon Well (Longjing), Biluochun, Sencha (in Japan).

White Tea

Oxidation: Around 10–30%.

Processing: Very minimal — leaves are simply withered in the sun and gently dried.

Flavor: Subtle, sweet, with notes of honey or hay. Gains complexity as it ages.

Examples: Silver Needle (Baihao Yinzhen), White Peony (Baimudan),Yunnan Ancient White Tea.

Yellow Tea

Oxidation: About 10–20%.

Processing: Similar to green tea, but with an extra “sweltering” step where leaves are gently steamed under a damp cloth, allowing slight oxidation.

Flavor: Smoother than green tea, less grassy, with a mellow, rounded taste.

Examples: Junshan Yinzhen, Huoshan Huangya.

Oolong Tea

Oxidation: 30–70% (between green and black tea).

Processing: Leaves are withered, shaken or “bruised” to promote partial oxidation, then heated to stop the process, rolled, and dried.

Flavor: Very aromatic, ranging from floral and fresh (green-style oolong) to roasted and toasty (dark oolong).

Examples: Tieguanyin (Iron Goddess), Da Hong Pao (Wuyi Rock Tea), Taiwanese High Mountain Oolong.

Black /Red Tea

Oxidation: 80–100%.

Processing: Leaves are withered, fully rolled to break the cells, allowed to oxidize completely, and then dried.

Flavor: Rich, malty, sweet, sometimes fruity. Smooth, with little bitterness.

Examples: Keemun (Qimen), Dianhong (Yunnan), Lapsang Souchong (smoky style).

Note: In Chinese, this is called “Hong Cha” (Red Tea) because of the reddish color of the infusion. But in English, it is universally known as Black Tea

Dark Tea

Oxidation: Post-fermentation by microorganisms (beyond simple enzymatic oxidation).

Processing: After initial drying, the tea is piled and allowed to ferment with the help of microbes, sometimes for months or years. Often pressed into bricks or cakes.

Flavor: Earthy, woody, mellow, sometimes with notes of dried fruit or even camphor. Improves with aging.

Examples: Pu-erh Tea (from Yunnan), Liu Bao, Anhua Dark Tea.

Read More